|

||||

|

A Feast of Feminist Art

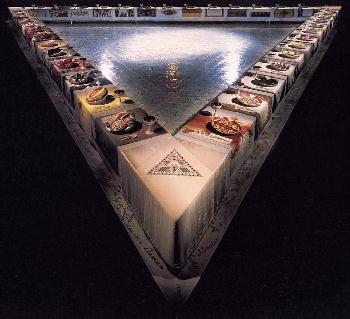

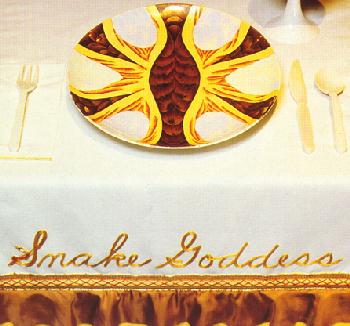

By Carey Lovelace Three years ago, philanthropist Elizabeth Sackler walked into Brooklyn Museum director Arnold Lehman’s office and dramatically placed on his desk a book about Judy Chicago’s feminist megasculpture “The Dinner Party.” “Would you like it?” she asked him. “Oh, thanks,” he replied, “I don’t have that.” “Not the catalog,” said Sackler. “I mean ‘The Dinner Party’ itself.” It took awhile for the stunned Lehman to recover. “The Dinner Party” is an immense environmental artwork, at the center of which is a 48-foot-long triangular table with individual plates representing 39 famous women in history or mythology. Not only is it large in size, but the piece has sparked controversy ever since it premiered at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979. “Brutal, baroque, and banal,” seethed The Village Voice. “Kitsch,” complained critic Robert Hughes. What particularly incited some critics were plates that featured three-dimensional “vulval” shapes. But “The Dinner Party” was also revered by many, young and old, and so popular during its 1980 run at the Brooklyn Museum that it was held over. And maybe that’s one of the reasons why Lehman said “yes.” Besides, Sackler offered to donate more than “The Dinner Party” — she’s funded a whole new wing of the museum, which will open in 2006 as the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Designed by Susan T. Rodriguez of Polshek Partnership Architects, it will occupy 8,300 square feet on the fourth floor of the renowned institution, and will include a small lecture hall, an exhibition space, archives, a women’s-history database and, hopefully, a permanent collection of feminist art. Radical Museology

Since feminist art has been underexhibited over the past 30 years, the Sackler Center comes off as a radical experiment in museology. “Of the liberation movements for which the late 20th century will be remembered,” New York Times critic Holland Cotter has noted, “few have been as disparaged as feminism.” He added that most people in the art world “seem incapable of talking about [feminist art] without condescension, as if it were some indiscreet adolescent episode best forgotten.” “The Dinner Party” itself languished in storage in New Mexico for nearly two decades. Sackler, a Ph.D. in public history who has been active in repatriating Native American ritual objects, struck up a friendship with Chicago in 1988, and then became one of several champions seeking a permanent home for what many regard as the feminist art movement’s most iconic work. The hope is that with “The Dinner Party” as its centerpiece, the Center will draw long-awaited attention to the 1970s, an era when scores of other women were also producing important feminist artwork. Also, in an adjacent “biography gallery,” it will focus the spotlight a bit away from art and onto the larger arena of women’s history with annual exhibits showcasing groupings from among the 1,038 mythic and actual figures celebrated in “The Dinner Party.” “Pharoahs, Queens and Goddesses,” the first such exhibit, will explore the cultural contributions of ancient women, borrowing 25 pieces from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive antiquities collection. On-site computer terminals will offer lively interactive pages about “The Dinner Party” women and feminism in general. A Feminist “Biennial” Though the Sackler Center is about “mainstreaming” feminist art, its funder is quick to add, “I don’t want it to lose its gumption.” The inaugural show will feature works of “neo-feminism.” Organized by the Sackler Center’s already-hired curator, Maura Reilly, along with art historian Linda Nochlin, this first major evaluation of the post-1990 global explosion of gender-aware women’s art will focus on work that’s transnational, and perhaps even transgender. “I’ve heard it called the first feminist ‘biennial,’” says Reilly — “biennial” being a showcase of talked-about artists. Feminism is coming into a “new and revived chapter,” adds Nochlin, whose world-renowned 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” challenged women’s invisibility in art history. Reilly is considering for the exhibit such artists as Reem Al Firm, a Saudi Arabian woman for whom just the making of art is feminist because she has to do so in secret, and South American artist Doris Salcedo, “who does work on issues around the Colombian drug trade,” says Reilly. “We need to get over a North American bias of what constitutes feminism.” Cornelia Butler would agree. More Global Than We Knew Around the same time as the Brooklyn show, a long-awaited survey of art from the 1970s related to the women’s movement, curated by Butler, will open at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s (MOCA) huge Geffen Center. Los Angeles and New York — where demonstrations were held, museums picketed and key works composed — have traditionally been seen as the centers of early women’s-movement art. Yet in Butler’s upcoming show, titled “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution,” about half of the 100 artists will be from outside the U.S. As Butler studied the crucial time period the show is covering, from 1965–80, she discovered that art feminism was more global than she had realized. She plans to exhibit English artists Sally Potter, Rose English, Cosey Fanni Tutti and Margaret Harrison, as well as artists from Poland, Italy, Chile, Brazil, Canada, India, Algeria, Germany and Scandinavia. The result, alas, may leave the scores of talented U.S. artists who came up through the 1970s disappointed. “It’s not going to be the show of American feminism that I think everyone wants,” she sighs. Even as the definition of feminist art is changing, and our understanding of who those art-makers are, its political message of empowerment and egalitarianism remains. Sackler initially didn’t want the gallery named after herself, but Chicago talked her into it because “women should take credit for what they do.” Now Sackler’s worldview extends beyond art: “I have a vision,” she muses, “of a young girl walking down the hallway and seeing an “Elizabeth … Center of Feminist Art” with a work of art by Judy … that is all about women.”

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||