|

Toronto Website Design & Toronto SEO

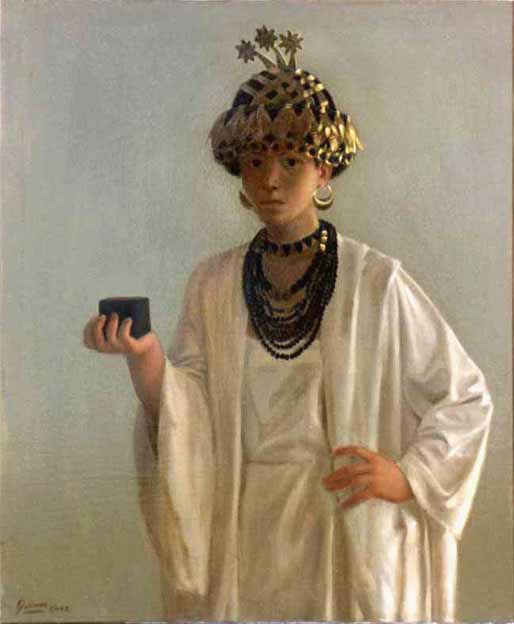

Women of Power:

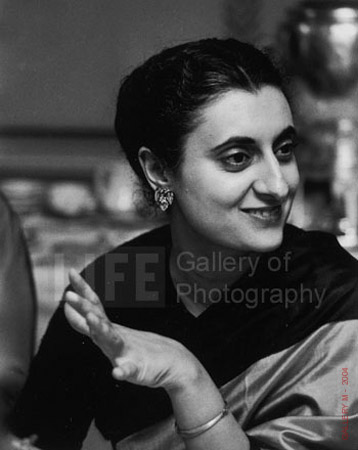

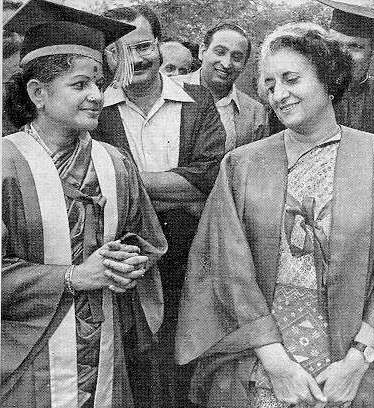

From Ku-Baba to Indira Gandhi

What makes a woman of power?

Olivia Ward - March 2006.

In the third millennium BC, a legendary female warrior named Ku-baba took charge of the great city-state of Ur, and changed the shape of the Middle East at the dawn of civilization.

For the next 4,500 years, however, women struggled to gain a foothold on the global ziggurat of political leadership that remains a male stronghold.

Deified and demonized, women like Britain's warrior queen Boadicea, Egypt's Cleopatra, Russia's Catherine the Great and Britain's "Virgin Queen" Elizabeth I left sensational legends behind them.

More recently, Golda Meier, Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher became icons of female power in Israel, India and the United Kingdom, respectively.

Now, women leaders have taken their places atop the political tables in Germany, Jamaica, Liberia, Chile and other countries.

Women's advocates are heralding it as the beginning of a new era. But those who monitor political equality say power is still the province of men throughout much of the world, and "women on top" remains a bad music-hall joke.

"Ten years after the Beijing declaration (on women's rights), we still have far to go on the actual representation of women at the highest levels of national and international leadership," UN Deputy Secretary General Louise Frechette, told the world body's Commission on the Status of Women last week.

"That includes the UN itself, the charter of which proclaims the equal rights of men and women," noted Frechette, the Canadian diplomat who will leave her post as the highest-ranking female official in UN history next month.

At the September 1995 Beijing summit on women's rights, world governments set a goal of having women in at least 30 per cent of seats in national legislative bodies.

So far, female candidates have won an average of only 16 per cent of such seats ? little more than half the target figure ? but that translates to nearly 6,700 seats worldwide, the highest total ever recorded.

Ironically, developing countries that have inherited fiercely patriarchal systems are leading the charge ? most dramatically in Rwanda, where women hold 48.8 per cent of parliamentary seats. The increase in female legislators may be primarily a legacy of genocidal war and the rampant HIV/AIDS epidemic that has killed many male political contenders ? and turned the population against male violence.

"Even men are getting fed up with men," says Vabah Gayflor, Liberia's minister for women's affairs, appointed by newly elected President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, the first African woman to hold such an office.

"They know how corrupt male politicians have been and also how destructive they are."

The new Liberian president will set a different style of governing, Gayflor says. "One that listens. When there's an outcry, there will be changes. It will restore the dignity of our country."

To some, the election of new women leaders like Liberia's, looks like a trend to watch.

But, says Noeleen Heyzer, executive director of the UN women's agency, UNIFEM, "it's really more of a test. In those countries, voters chose not just women, but specific kinds of women: ones who will keep their promises, be accountable and make sure that when money flows it goes where it's supposed to go. It's a major change in the political order."

Heyzer agrees that frustration and a desire for change were behind the recent successes of female political leaders. She calls it a "turning of the tide" against old-style corruption and violence.

Recently elected women like Johnson-Sirleaf, and Chilean President-elect Michelle Bachelet ? a former political prisoner ? have gained power in a new way, Heyzer points out.

"Not through depending on male lobbies, or being part of a male alliance. They're empowered by the grassroots, and the people on the ground will hold them accountable."

Already, Liberia is being touted as a symbol of hope for stability in western Africa. Unlike the fear-inspiring male leaders who dragged the country through 14 years of bloody civil war, Johnson-Sirleaf was embraced with relief as she met her supporters after the election. And the title that most often greeted her was "mother."

Down through the centuries, however, "motherly" was hardly an adjective one would use to describe the most famous women who wielded power.

The 15th-century Queen Isabella of Castille established the brutal Spanish Inquisition. The Florentine-born Catherine de Medici picked off her enemies with poison in 16th-century France. When "Dragon Lady" Empress Tzu-Hsi seized the Chinese throne in the mid-19th century, her ruthlessness left foes trembling. History remembers those rulers with awe rather than affection.

The rules are different today. And, with annual International Women's Day ceremonies set for Wednesday, the debate continues on the "proper" qualities a female leader should possess.

While men admire toughness, decisiveness and strength in leaders, they are wary of women who display those traits. Women themselves are divided. Some believe female leaders should have all those qualities, while others stress the "softer" traits of compromise, communication and fairness.

But the "feminine quotient" may be as much a burden as a blessing for women eager to reach the top.

It's not a glass ceiling those women are up against, it's a thick layer of men'

Laura Liswood, secretary general of the Council of Women World Leaders

"We shouldn't expect women to be kinder, gentler and more honest than men," says Rosemary Speirs, chair of Equal Voice, an action group for increasing women's political presence in Canada.

"But it's like the line about Ginger Rogers, who had to do the same steps as Fred Astaire, but backwards and in high heels. Women still have to be twice as good as men to succeed at the same jobs."

According to a poll by the Australian Virtual Centre for Leadership for Women, what most women value in their leaders is "individual self-belief and values, vision and determination to carry out the vision in decision-making skills."

For many would-be female leaders, however, self-belief is in short supply when running the gauntlet of men in power.

"It's not a glass ceiling those women are up against, it's a thick layer of men," quips Laura Liswood, secretary general of the Council of Women World Leaders and a senior adviser to the global investment bank Goldman Sachs.

"Men believe they are better at what they do than they are. Women have `negative illusion.' They don't think they are as good as they actually are. This lets men jump into the fray, raise their hands before they have something to say or take a job they are unprepared for. It means women hold themselves back from goals that they're eminently qualified to achieve."

Once women acquire a high political profile, says Speirs, they may also face the kind of stereotyping that seldom affects men.

"Belinda Stronach is called a political harlot. Sheila Copps was too aggressive, too loud. Women either suffer from too much negative attention or disappear because they're ignored."

But those who study women and power say a large part of the problem is more institutional than personal ? the relatively small numbers of females in political life.

In the recent Canadian election, women won less than 21 per cent of parliamentary seats, emerging with one seat fewer than in the last election.

"Women leaders emerge from the pool that exists in their countries," explains Liswood.

"The positive news is that there is an increasing number of women in parliaments and in ministerial positions. There are now over 500 sitting female ministers worldwide. That's where you will find the emerging women leadership candidates."

Women's advocates are convinced that with a "critical mass" of candidates, the numbers will change dramatically in their favour.

In Scandinavian countries, where the numbers of female politicians are higher, they point out, women leaders are already accepted as the norm ? so much so that, in Iceland, a teacher told of a boy in her class who asked whether he had any chance of leading the country, or if that was only open to women.

In spite of generally worse conditions for women in developing countries, female leaders have been more common there than in the West. But many of these women arose from prominent ruling families and came to power as the widows or daughters of male leaders. Their terms in office did little to improve the lot, or the political participation, of women in their countries.

North America has been especially resistant to female leadership. But that, too, may be changing.

In the United States, where no woman has ever run for president, both Republican Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Democratic Senator Hilary Clinton are being touted for the 2008 election, and polls show that 93 per cent of prospective voters have no objection to supporting a female candidate.

Canada was briefly governed by a female prime minister, Kim Campbell, who spent only four months in office in 1993. And female cabinet ministers are anything but a rarity.

Still, formidable barriers remain, especially in the U.S.

"Our national obsession is with dogs, hunting, hard-headed businessmen," writes University of Rhode Island historian Rosa Maria Pegueros in the Common Dreams website. "Now, we have a junkyard dog as president. Smell the testosterone .... At this rate it will be another 228 years before a woman will be elected president."

Yet male chauvinism alone may be less important than the political roadblocks facing American female presidential contenders. Many presidents come from the ranks of state governors, positions that are still overwhelmingly male, and others had their careers in the military, an institution in which few women are able to fight their way to the top.

But "the world is changing slowly and surely," says UNIFEM's Heyzer, who stresses that getting women elected isn't as important as electing those who will do something for women.

"The main difference now is that the women who have been elected mostly came from a constituency of women. They were supported by women, and they have to account to them. They are appointing women to important jobs and creating a political force. They're ready to rewrite laws and constitutions, so change isn't just a one-off thing."

|