|

||||

|

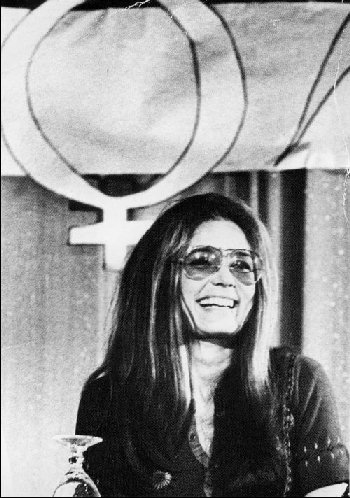

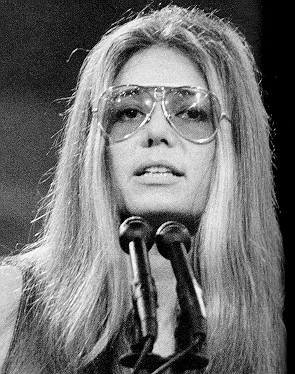

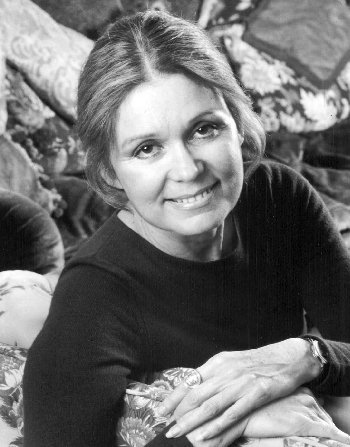

Fierce, Funny, Feminists: Gloria Steinem and Kathleen Hanna

Interview by Celina Hex. Without asking to, Gloria Steinem and Kathleen Hanna have been made de facto poster girls for the respective generation's women's movements - Gloria as the pretty, public face of the women's liberation movement, and Kathleen as the troop leader of the Riot Grrrls. So choosing to interview both of them was obvious. But getting these ladies together was no easy task. We originally wanted to photograph both of them for the cover, but between Gloria getting married and campaigning for the presidential elections, and Kathleen on the road with her band, Le Tigre, that proved to be impossible. In fact, just getting them to talk with each other was hard enough. But we kept hope alive. And after lots of finagling, we managed to do the following interview, with me on the phone from work, Gloria on her cell phone in a car on her to a meeting, and Kathleen by phone from San Francisco, as she was getting ready to set up that night's show. With such dedicated broads on OUR side, how can we not with the fight for our rights? Q: Have you two ever met each other in person? KATHLEEN: No. GLORIA: No. Q: Oh! But you know of each other ... GLORIA: Oh yeah, absolutely. KATHLEEN: (laughs) Q:Okay, so my first question is: How do you each define feminism? KATHLEEN: Gloria, you want to go first? GLORIA: Well, I think the dictionary is not bad, you know: the belief in the full social, economic, and political equality of women and men. I would just add "and doing something about it." And when you look at the effects of that simple statement, it's quite a transformation. KATHLEEN: I agree with what she said, and I would add that I also see It as a broad-based political movement that's bent on challenging hierarchies of all kinds in our society, including racism and classism and able-body-ism, etc etc. GLORIA: Yeah, I agree. That's the transformation - because once you take away the basic first step in a hierarchy, which is the passive/dominant of female/male, it challenges everything. Q: Kathleen, what did you know about Second Wave feminism when you were getting involved with Riot Grrrl? KATHLEEN: I didn't know very much, actually. I had just read "The Second Sex" by Simone de Beauvoir. And the only feminist thing i had ever been to, Gloria spoke at Bella Azbug - at the Solidarity Day in Washington, DC. I guess it was the late '70s, and I was 9 years old. GLORIA: Oh, that's so great! KATHLEEN: You were really incredible. My mom was a housewife, and wasn't somebody that people would think of as a feminist, and when Ms. magazine came out we were incredible inspired by it. I used to cut pictures out of it and make posters that said "Girls can do anything", and stuff like that, and my mom was inspired to work at a basement of a church doing anti-domestic violence work. And then she took me to the Solidarity Day thing, and it was the first time i had ever been in a big crowd of women yelling, and it really made me want to do it forever.

Q: Kathleen, did you feel that there were any differences between what Gloria Steinem and her generation of women were saying and what your generation of women were saying? KATHLEEN: Yeah, I mean 0 I'm going to admit to a mistake right now - the thing is that, when I first started, I was on shaky ground in terms of my identity and my personality. And in order to feel like I was a strong person, I kind of based myself in opposition to what I perceived as being Second Wave feminism, which was really ignorant, and based on all of the stereotypes. Like that they have hairy legs and they are anti-sex and so on. And I was like, "I'm a SEXY feminist, and I'm going to wear makeup and blah blah blah." Then, when i actually started delving into the history, I realized that I was playing into stereotypes, and that i didn't need to base myself in opposition to my perception of the past. Instead, I needed to learn from it and grow from it and seek out mentors and a continuation of things that had happened before, as opposed to positing myself as the new hip feminist product to be consumed. I was really playing into a lot of bullshit capitalist ideology that i now realize was stupid, and now I'm seeking out more information. GLORIA: You know, it's interesting listening to you, because, though I knew less about the suffragists than you know about the Second Wave, I did the same thing of positioning myself in opposition to them, because I had heard they they were these puritanical, sexless bluestocking folks. And that wasn't right either - look at Emma Goldman, look at Victoria Woodhull and the Free Love Party. I think that what happens, in a deep sense, is that society sees the relationships between men and women, and even between women and women and men and men - all sexual relationships- as having to be passive/dominant. So, if you're talking about equality, they think you must be against sex. KATHLEEN: Right. GLORIA: It's been dramatized for me because I was saying that the same things in the '70s, wearing miniskirts and being percieved as a slut. now, saying the same things, I'm percieved as being anti-sex. think the equality part has sunk in, and they've stopped confusing us with the sexual revolution. KATHLEEN: (laughs) GLORIA: So it's super important to look at the real women, and not just the stereotypes. Q: Gloria, when did you first hear about Riot Grrl, and what did you think about it? GLORIA: I think that the first thing i heard about was Positive Force, from talking to young women and music fans in Washington. It sounded so admirable, using culture in a radical way to make radical social change. And later on, hearing about the Riot Grrrl convention, it sounded like a new, music-based version of consciousness-raising. So although I think it's true that music is really generation-bound - there's no replacement for what you grow up with-I heard about the political side and the effort to make a place inside that punk boy culture. I was really fascinated by it and applauded it. Q: Why wasn't the Riot Grrl movement covered in Ms. magazine earlier on? GLORIA: I don't know the answer. I think perhaps because it's true that older feminists don't always recognize feminism when it comes in a different form. Perhaps because it was viewed as the province of Rolling Stone. You know, there's not that much music coverage in Ms.

Q: How did you feel about that, Kathleen? Did you feel that older feminists weren't paying enough attention? KATHLEEN: No. I mean, I just feel like women of all kinds are really strapped for time. And I was really flattered when I was actually in Ms. Q: Right, a couple of months ago. KATHLEEN: But I was wondering, Gloria, what music was going on when you were first coming of age as a feminist? And were there feminist bands around that you were into, or feminists musicians? GLORIA: Well, it was the beginning of singer/songwriters like Judy Collins, and all the many folkies of that generation. But there wasn't the variety or depth of lyrics. I really think that now the women singer/songwriters have created a whole literature of consciousness-raising and politics and emotions that is as deep and important and probably more influential in a populist way than many of the books that came out at the beginning of the Second Wave. Q: Kathleen, do you think music is still important to the feminist movement? KAHTLEEN: Yeah, of course. Feminist art has always been important. Whether it's Judy Chicago or Eve, we're out there doing something. It's interesting that Gloria was comparing music with books, because part of what I'm trying to do in my new band, Le Tigre, is to make feminist pop music. We're trying to turn a lot of younger women onto certain books. We sing about books, actually, and we sing about feminist theory. GLORIA: I don't know whether this makes sense or not, Kathleen, but the first dawning for me that there was a different kind of joyous, defiant message coming out in music was Cyndi Lauper singing "Girls Just Wanna Have Fun", and seeing the impact that it had on her female listeners. We made her one of the Ms. Women of the Year sometime in the '80s. KATHLEEN: Yeah, i remember that cover. It was great. GLORIA: People were sort of shocked by it. But it seemed to me to make perfect sense.

Q: At the same time that Cyndi Lauper was getting so popular, Madonna was getting really popular, too. How did you each feel about her? GLORIA: What interested me about her was that, in the beginning, she took all the symbols of Marilyn Monroe - things that had been used to make Marilyn Monroe something of a victim - and said, "I'm taking control of these symbols and I'm nobody's victim." I thought that was great, and also the reason why Marilyn Monroe's fans tended to be young and middle-aged men, while Madonna's fans tended - especially in the beginning- to be quite young women. I just think they were so relieved to see a woman who was in control of her sexuality and having a good time, and not being a victim.

Q: How about you. Kathleen? KATHLEEN: I don't know. I'd rather talk about Shulamith Firestone than Madonna. Q: She wasn't important to you at all? KATHLEEN: Well, I mean, unless you live under a rock, you can't really claim that Madonna wasn't important in some way, shape, or form. But at this point I just look at her as a cultural appropriator, and I'm not that excited by her work anymore. But I also don't want to publicly say something really mean about her. |

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

Q: But, when you were younger, and she was first coming out, how did you feel about her? KATHLEEN: I thought she was really cool, I wanted to be like her. You know, like in the Desperately Seeking Susan-era, she was just really hot, and who didn't want to be like her? But it's the same as looking in Seventeen magazine and trying to look like those girls. Also, I went to college in the early '90s, and everybody was getting into popular culture and theorizing about popular culture, and there's something interesting about that, and then there's something really stupid about it, where it just goes too far, and you're like, "I want to talk about Shulamith Firestone and Ellen Willis. I don't really want to talk about Madonna." GLORIA: So we've changed places! KATHLEEN: Yeah. (laughs) GLORIA: Actually, I agree with you, because everybody knows Madonna, and to the extent that this is the "F-Word" interview, people need to know about Shulamith Firestone. KATHLEEN: Right, I mean, she wrote a best-selling book, and so many people don't even know who she is! GLORIA: And her book meant even more to me than the other early feminist books. Q: I think it's interesting that both of you have utilized pop culture to take your message to the masses-Gloria started Ms. and Kathleen's had various bands and zines. How important is pop culture, and how important is political action? GLORIA: Everything is important. And in my case, my profession was being a writer, and-especially when it came to women's magazines-I just wanted to work for one i read. And there weren't any. There were some that had an article now and then, but there was nothing I wanted to read regularly, and nothing that talked about changing the world, not just changing your eyeliner, you know? So we didn't do any market research or anything like that, we were just getting together as feminist writers and editors and trying to start something that we ourselves wanted to read. KATHLEEN: Well, I think it's important to speak out to people who don't have access to underground stuff. Like, I know in the Second Wave, before Ms., there were all these broadsides and fanzines, and some of them were really incredible, and some of them were really counterproductive. But I think underground stuff and more accessible stuff is all important, and it's especially important not to forget that everybody doesn't have access to movement literature that's just circulated amongst twenty people. Q: Kathleen, the people that you've been mentioning so far are all from Gloria's generation. Do you feel that was when the most important feminist work happened? KATHLEEN: I feel like every time has been the time for really important feminist work. I'm just really obsessed with Second Wave history, because things aren't going to change until we have a continuum, and i feel like i need mentors. I need to learn from people's mistakes, instead of feeling like i have to reinvent the wheel over and over again. //like, I know that Gloria has experienced controversy and scandal in her career, and I've had similar things where people were disguising backbiting and horizontal oppression as valid criticism. And I need to know how, as an FF - Famous Feminist - to deal with these things. I need to see the graceful ways that other women have dealt with that. GLORIA: Yeah, I agree. Although I'm not suggesting that I did know how to deal with it - I often dealt with it poorly- but I do think that I would have been helped by learning from other people. I think what's helped me, too, is to realize that in the same way that men criticize the so-called weak member of the group, women tend to criticize the so-called strong member of the group. It's one of the many ways we've been taught to internalize and to perpetuate gender roles. KATHLEEN: Exactly. Q:How did you feel about getting involved in feminism in the '70s, Gloria, and suddenly becoming Queen of the Feminists. GLORIA: There is no Queen of the Feminists, by definition. Q: Right, but from a media perspective, you were "It". GLORIA: Well, you know, on the one hand I was working in the media, and on the other hand I was trying to avoid being singled out by always speaking with another woman, by refusing to do interviews unless there were other women-racially diverse women-who were (also) part of the article or interview. It wasn't always successful you know- Newsweek did an early cover story about me, for instance, and I wouldn't pose for photographs, so they just took one with a telephoto lens. I think the challenge is to figure out how to use public recognition to convey some message. A simple-minded example is that, when somebody asked me for an autograph I used to say no, because I thought that institution was such a hierarchy in itself, but that was seen as unfriendly, so i began to ask people to trade autographs with me. And I think, small though that is, it conveyed a different message. So that's the challenge and the fun, to try to take old bottles and put new wine in them. Q: Kathleen, you've had a very similar situation. Riot Grrrl refused to talk to the media at all, and you still ended up in Newsweek. How have you felt about all of that? KATHLEEN: It was really terrible at first, 'cause I didn't want to be the leader; it was obviously a community of a lot of different women working on different fronts. I felt really embarrassed and humiliated by being singled out in that way, and (as a result) I was sometimes perceived as a traitor, even though it wasn't my fault. But, like Gloria, at a certain point I just had to accept it and think, "What can i do with this?" It's funny, 'cause when I sign autographs I write "Born in Flames by Lizzie Borden", a movie that I think is genius, that I think all women should see. So I use my autograph as a way to advertise that movie. Or I'll write down just a book, like The Dialectics of Sex by Shulamith Firestone, or Letters to a Young Feminist by Phyllis Chester, or No More Nice Girls by Ellen Willis, and then sign my name. GLORIA: Oh that's a good idea- to use autographs to send a message! That's good! Q: I know we're having a happy love-fest here, and that's great, but I want to bring up some things that I think you might have different opinions on. For instance, back in the 90s, Riot Grrrls took to wearing girlie dresses and sporting Hello Kitty back packs and trying to reclaim the idea of girlieness, while a lot of older feminists criticized the "baby doll look" as infantilizing women. How did you both interpret the Riot Grrrls' take on "girlie"? GLORIA: Well, I'm trying to remember. It's always seemed to me that the point was to be able to wear what you fucking well please, as I'm often quoted as saying (laughs). On the other hand, there are some symbols that were so forced on us in my youth that it's hard for me to understand them as a free choice. Like girdles, garter belts, and very high heels that you can't run in...but even if I felt internally uneasy, I don't believe I ever was publicly critical of something another woman said she had freely chosen. KATHLEEN: For me, some of the youth-oriented stuff, of dressing like a little girl, was also about women who had to numb out most of their childhood due to sexual abuse. Reclaiming that. And saying "I deserve a childhood and i didn't have it, and now I'm going to have it." It was also about being freaks, being punk rockers, being people who are oppositional to the whole American system, and not wanting to look like adults and our parents, who we saw as fucking up the world. And it was also when that Carol Gilligan book came out about how girls lose their self-esteem around twelve or thirteen, so everyone was talking about being nine. Like trying to go back there, and remembering what it was like when we werefriends with each other, and we weren't totally competitive, and we were creating our own weird games and ideas. But you know, I'm 31 now, and I'm not really interested in dressing like a little girl anymore. I find it infantilizing, too. And I never liked Hello Kitty. I always joke that I'm going to be 80 years old with my Hello Kitty cane that I'm going to hit people with... GLORIA:I agree-I think we need to explore and reclaim, and the question is

not so much what we choose, but that we have the power to choose it. I'm sure

I made feminists older than I feel uneasy as I wandered around in the '70s in

miniskirts and boots with a button that said "Cunt Power". But I still think

we ought to be able to do it, there's a purpose to doing it.

Q: You came of age in two different sexual generations. Do either of you think that women still have a long way to go, baby, when it comes to having sex? GLORIA: I hope and believe that it's much better than it was then. We used to have a sign up on the bulletin board at Ms. that said, "It's 10pm, do you know where your clitoris is?" That's no longer necessary. KATHLEEN: (laughs) Q: Kathleen, do you think that the sexual revolution has been fought and won? KATHLEEN: No. I mean, as long as sexual abuse still exists, and as long as hatred and violence against lesbians still exists, there is no sexual freedome for everyone. And hate crimes against lesbians and transgendered people is, I think, such a huge impediment to people being able to do what they want. For everone - straight, gay bisexual, trans, whatever - these are things that impede everybody's ability to enjoy themselves and be joyful sexually. GLORIA: I agree. We're still fighting the revolution of trying to separate

sex and violence. If we could just agree not to use those words together in

one phrase, as if they had to come together or were equally a problem, it

would be a big advance. In the '70s, we were trying to say that rape is not

sex, it's violence. Now some of us are trying to say that pornography is

erotica. Not that either should be censored, but pornography-which, since

porne means female slavery, means violence against women-should be looked at

in the same way, say, as racist literature. You may want to preserve the

right to publish it, but you also may want to use your First Amendment rights

to protest it.

In the '70s, people confused the sexual revolution with feminism, and the

sexual revolution really was about making more women sexually available on

men's terms. Now there's a better understanding of what feminism means

sexually, but there's great resistance to it, and it comes from the same

source as the resistance to end violence against gays and lesbians, as

Kathleen points out - resistance to the right to separate sexuality from

reproduction. Since women need to do that to preserve out health and

freedome, regardless of our sexual choices, and since gay men and lesbians

are also using sexuality as a form of expression-which is what it is, as well

as a form of procreation-we have to understand that the resistance is all

connected, and has to be fought at the same time.

Q: Well, I'm glad that you raised the issue of pronography, because that's another thing that has been rather divisive to feminists over the years. Kathleen, what's your take on that? KATHLEEN: In terms of pornography, one of the main things that I'm afraid of is feminists working with the police and with the government to enact laws that will hurt sex trade workers, or that will hurt women who work in the pornography industry. That's something KacKinnon and Dworkin have been involved in that really frightens me. GLORIA: We may have a difference of opinion on pornography, but I just want to make sure that it's understood that they never advocated censorship. KATHLEEN: But they did try to enact, in Washington State, laws that required sex workers to be fingerprinted and go into the police department. GLORIA: No, they did not. As far as I know, what they supported was the ordinance in Minnesota, and it never... KATHLEEN: It never passed. GLORIA: I mean, we can check, but I don't believe that they would suggest anything like fingerprinting. KATHLEEN: Well, it was actually the police that suggested that part of it, but the idea was to cut down on child pornography, and to make sure that all the women who were in the sex industry actually 18. GLORIA: Yeah, I doubt very much (that Dworkin and MacKinnon had anything to do with that). Hardly anybody is as misunderstood as Andrea. KATHLEEN: I think she's contributed really, really important scholarship, but i mean. I'm getting this from a lecture that I was at.... GLORIA: A lecture by? KATHLEEN: By Andrea Dworkin. And she was talking about the legislation in Washington State that they were working at the time to enact. And I don't know if it ever passed or not, because I moved. GLORIA: As in Minnesota, I think the legislation they were supporting

essentially said that, if pornography could be proved to have contributed to

a crime to the satisfaction of a jury, then there could be a civil penalty

not a criminal remedy. We should look it up, it'd be interesting to check all

this*.

Q: How do you two feel about men? Can they ever be as feminist as women? You've probably both been accused of reverse sexism... GLORIA: Well I've been accused of everything. KATHLEEN: (laughs) GLORIA: Liking them too little, too much. But of course, biology is not destiny, and there are some men who are better feminists than some women. But it's also true that it's justified to have anger against men who treat you badly, and who undermine or denigrate or create hierarchies or hurt people. There's nothing wrong with healthy angry. Indeed, depression is angry turned inwards. KATHLEEN: Well, I don't think sexism is going to change unless men start to investigate the construction of masculinity and how to move outside of the boundaries. And I think that, while sexism hurts women most intimately, it also damages men severely. Q: Gloria, we all know that you just got married. Kathleen, do you think you'll ever get married? KATHLEEN: I don't know. I don't think about these things. We should all just be having a good time. *In 1983, MacKinnon and Dworkin wrote an anti-pornography civil rights ordinance for the city of Minneapolis. This law would have permitted individuals who were harmed by pornography (whether by forced participation or other means) to sue the pornographer in civil court. The Minneapolis city council passed it twice, but it was vetoed both times, and was finally declared unconstitutional in higher courts in 1985. In 1988, a version of the Dworkin-MacKinnon Ordinance was approved by voters in Bellingham, Washington. It was struck down by Federal District Court Judge Carolyn Dimmick. We did not locate any references to fingerprinting prostitutes in the Washington case.

|

||||

|

|

|

||