|

||||

|

The Cyborg, the Scientist, the Feminist & Her Critic

By Krista Scott - 1997.

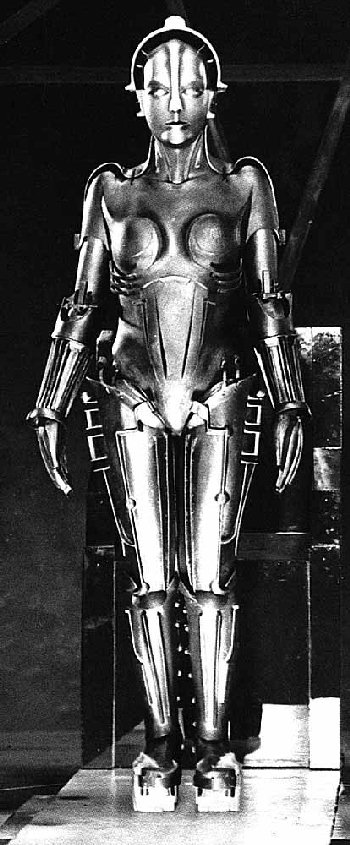

Introducing the CyborgIn her article, "A Cyborg Manifesto", Haraway attempts to create what she calls "an ironic political myth" which combines postmodernism with socialist feminism. Central to her myth is the image of the cyborg, which is "a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction." The cyborg for Haraway is both a metaphor for the postmodernist and political play of identity as well as a lived reality of new technology. As she says, "I am making an argument for the cyborg as a fiction mapping our social and bodily reality and as an imaginative resource suggesting some very fruitful couplings." The role of irony in the cyborg myth cannot be overlooked, since for Haraway it implies a sense of agency in the world around us: "Acknowledging the agency of the world in knowledge makes room for some unsettling possibilities, including a sense of the world's independent sense of humour? [it] makes room for surprises and ironies at the heart of all knowledge production?" The cyborg, then, stands for shifting political and physical boundaries which, in its interface with us and the world around us, often wittily pulls the rug out from under what we perceive to be "natural".

Nature-Culture: Them and UsIt is often argued that technology and its partner, civilization (which is a highly arguable concept in itself) are ways of subduing nature and bending it to human will. Nature-culture is a familiar adversarial binarism which has fuelled many world events and ideologies, from colonialism to Freudianism. Haraway notes: "The distinction between nature and culture in Western societies has been a sacred one; it has been at the heart of the great narratives of salvation history and their genetic transmutation into sagas of secular progress."

[The film] Synthetic Pleasures [captures] examples of the way in which we humans are attempting to take conscious control of our environment and our bodies themselves? In Japan, [director IaraLee] finds vast indoor pleasure domes: ski slopes built with artificial snow, beaches washed with artificial waves, golf driving ranges where the players are stacked one above the other up to the sky. On the Internet, [she] visits Web pages where strippers perform on demand. It is a cliché to visit Las Vegas and find artificial volcanoes and pyramids. But what about the notion that someday society will be organized along similar lines, and like gamblers we will never go outside, or know night from day, or desire anything that can not be ordered over the phone? Yet in Haraway's paradigm, "nature" has the last laugh as it melds with technology and the borders between become indiscriminate. The fact that we can create virtual partners does not eradicate or even control the sexual urge; in creating artificial "natural" environments we reveal our delight in retaining them as part of our lives. "Nature", as always, is not subdued but subverted. Not only does Haraway reveal the ambiguity and irrelevance of nature-culture binarisms in the cyborg age, she also reveals that "natural" was never even so. She charts the differences between "comfortable old hierarchical dominations" which have the appearance of "naturalness" since they are so embedded in our Western cultural consciousness, and the "scary new networks" which sprouted after the Second World War. Here are a few of her "before-and-after" pairs:

Haraway's chart allows her to point out the problems with facile assumptions of a more "natural" past. "[The] objects on the right-hand side cannot be coded as 'natural', a realization which subverts naturalistic coding for the left-hand side as well. We cannot go back ideologically or materially. It's not just that 'god' is dead; so is the 'goddess'". Haraway's vision critiques the false organic self which some, particularly radical, feminists use as a basis for affinity and identity. Affirming that she'd "rather be a cyborg than a goddess", Haraway "doesn't see much point in the so-called goddess feminism, which preaches that women can find freedom by sloughing off the modern world and discovering their supposed spiritual connection to Mother Earth." (Ironically, though Haraway rejects the idea of the goddess in favour of the cyborg, this kind of poly-politic was echoed 5000 years ago in the figure of the Sumerian goddess Inanna, who stood for liminality and boundary crossing. A perpetual adolescent hovering between child- and womanhood, her aspects were those of transition 'dawn and dusk' and she was able to frequent heaven, earth and underworld.) However, Haraway does not limit her critique of an imagined "natural" to feminists; she is consistent in her opposition to false organics in other fields, particularly the scientific. In the same book as "Cyborg Manifesto", she includes other essays which critique sociobiology, animal research and others for embedding "functionalist and capitalist economic" terms of reference in their observations of "[o]rganic form [as] hierarchical and physiological co-operation and competition based on ?natural? domination and division of labour."

Indeed, many would be surprised to know that what they conceive of as their "natural" organic self is closer to the cyborg than they think. Radiation is a good example. We tend to think of radiation as something bad, unnaturally generated, and dangerous, associated with dubious nuclear power generation projects and atomic bombs. Yet the human body in fact contains about ten to twelve kiloBecquerels of naturally occurring radioactive potassium (40K) in the intestines, uranium (238U) and carbon (14C) in bones. Just from living on earth we receive cosmic radiation at the rate of approximately two thousand microSieverts per year. Should we choose to be cremated upon our demise, the resulting residue has a high enough activity level to qualify it for disposal in a radioisotope waste facility. And what could be more charmingly vegan and non-threateningly organic than the humble banana?until one realizes that ingesting said banana means ingesting radioactive potassium since one in every ten thousand potassium atoms is a radioactive isotope! In other words, the line between what we often think of as natural and unnatural gets fuzzy when we examine many of the processes and substances in our body and environment which occur in the normal course of things, unaided by scientific or technological developments. When we examine more closely what we take for granted to be natural, we see that the qualities which we associate with being so are not necessarily present.

Or, conversely and perversely, our bodies have qualities and processes which we sometimes perceive as unnatural or a product of technology. Is my weightlifting hobby "unnatural", given that I consciously and deliberately?through use of machinery?manipulate my body? Therefore, says Haraway, feminists cannot use an imagined organic ontology as a point of politics or engage in "knee-jerk technophobia" because there simply isn't such a "natural" self. We have come too far from the primordial soup to return. As Haraway notes, "[w]e cannot pretend we live on some other planet where the cyborg was never spat out of the womb-brain of its war-besotted parents in the middle of the last century of the Second Christian Millennium." Thus, reasons Haraway, "if women (and men) aren't natural but constructed, like a cyborg, then, given the right tools, we can all be reconstructed." As a result, "[b]asic assumptions come into question? Maybe humans are biologically destined to fight wars and trash the environment. Maybe we?re not."

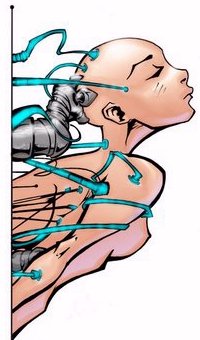

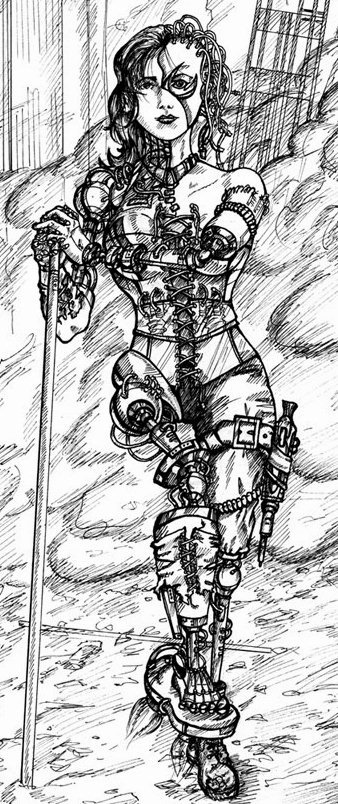

The Cyborg: Boundary Break, Breach and BlurWith its indiscriminate boundaries, the merger between nature and civilization gives us the cyborg. The cyborg is "a cybernetic organism, a fusion of the organic and the technical forged in particular, historical, cultural practices." Yet the cyborg, according to Haraway, resists what has gone before; it is more than the sum of its parts. "The cyborg incarnation is outside of salvation history. Nor does it mark time on an oedipal calendar, attempting to heal the terrible cleavages of gender?" In addition, The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity. Since the cyborg does not exist as nature or culture, but is rather a hybrid of both and more, it is not limited by traditional binarisms and dualist paradigms. The cyborg exists as a kind of unfettered self, like the lines in a Jackson Pollock painting which were freed of the necessity of figuration in their random scribblings. The cyborg is polymorphous perversity. It is both visionary in its polyvocal play and troubling in its origins: Haraway sees the cyborg as "the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism." Haraway feels that there are three major boundary breakdowns in the formation of the cyborg. The first is between human and animal. She notes: Biological and evolutionary theory over the past two centuries have simultaneously produced modern organisms as objects of knowledge and reduced the line between humans and animals to a faint trace re-etched in ideological struggle or professional disputes between life and social science. As we increase our knowledge about genetics and their manipulation, the idea of humans as the perfection of creation diminishes, or at least sobers us up a little from our drunken spree of supposedly sacred stewardship---although it's still clear that we?re on top of the political food chain. However with the development of transgenic organisms, the idea of genetic integrity/unity of the organism is called into question. Haraway notes wryly: "The organism has been retooled materially in the New World Order, Inc. as well as semiotically."

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

PPL Therapeutics, which created a global furor earlier this month by cloning an adult sheep, plans to get into the equally controversial business of animal-to-human transplants, managing director Ron James said yesterday. Mr. James said PPL would start research on genetically engineering pigs for use in xenotransplants. The research is likely to concentrate on pig hearts, which are a good match for humans in terms of size and function. PPL specializes in creating transgenic animals, which have some human genes and can produce human proteins in their milk. The British government has declared a moratorium on xenotransplants until all the dangers, such as introducing an unknown virus into people, are studied. But Mr. James said this would not affect PPL. "By the time we get around to trials, either the moratorium would have been lifted or we will be able to do them somewhere else." In Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMousetm, Haraway's latest publication, she presents us with the figure/metaphor of the OncoMousetm, the world's first patented animal. Oncomice are designed genetically to reliably develop cancer so that researchers can study processes and treatments for humans. "Like other family members in Western biocultural taxonomic systems, these sister mammals are both us and not-us; that is why we employ them." The OncoMousetm is more than a patented organism, though that fact alone is cause for thought; OncoMousetm represents a human-animal symbiosis/merger of corporate technoscience. As we manipulate its reliable cancers, we inscribe its brief existence upon ourselves. Japanese scientists have managed to insert large chunks of human DNA into mice, an astonishing breakthrough that will allow a new generation of research into genes, birth defects, and genetic diseases. Researchers have put human DNA into mice for years, but not on this scale. Some of the newly developed mice have a complete human chromosome?one of the rod-like structures that hold genes?containing some fifty times the amount of DNA scientists have been able to transfer before. The second boundary breakdown is between organism and machine. Not only are our household machines, such as bathroom scales which talk or VCRs which record programs automatically, becoming more lifelike and taking on personalities, but humans are coupling with machines for medical purposes: pacemakers, dialysis, artificial limbs and joints, hearing aids. In addition, creating an organism-machine interface need not require complicated medical equipment; weightlifters routinely manipulate their body's characteristics with machines and telemarketers wear their telephone headset snuggled close to their brains. It is futile to rage against the encroachment of machines in the late 20th century; like the revenge-seeking household appliances from an episode of the Twilight Zone, machines take on life and infiltrate our space whether we like it or not. The latest version of my computer software is "smart" enough to know that when I type "teh" that what I really mean is "the", and in fact to write this sentence required some minutes of wrangling with the computer so that it would even allow me to leave "teh" the way it was. The third boundary breakdown is between the organic and in organic. "Marked with the stigmata of a dream, a symptom, and an ordinary research project? scientific efforts to splice carbon-based life forms to silicon-based computer systems take many shapes, from the merely ideological to the technically productive." With the frenzied research into the development of bio-CPUs which utilize organic virus-like components, the microelectronic revolution will become ever more invisible. Haraway notes: "Our best machines are made of sunshine; they are all light and clean because they are nothing but signals, electromagnetic waves, a section of a spectrum? People are nowhere near so fluid, being both material and opaque." Far from the big grinding gears and metal millstones of yesteryear, today's machines carry almost infinite amounts of information on a tiny chip hidden somewhere behind an attractive facade. Machines have become Ariels to our Calibans; we are the golems made of mud and machines that which breathe life into the world around us. This ethereal invisibility renders machines potent weapons: "They are as hard to see politically as materially. They are about consciousness?or its simulation." Thus Haraway's cyborg myth is "about transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities which progressive people might explore as one part of needed political work." The myth captures the "contradictory, partial and strategic" identities of the postmodern age. Yet Haraway aims for more than a pleasant science fiction, more than what Teresa Ebert critiques as a bourgeois fantasy. She points out that: "Who cyborgs will be is a radical question; the answers are a matter of survival. Both chimpanzees and artefacts have politics, so why shouldn't we?" Haraway feels that the cyborg myth has the potential for radical political action as it frees feminists from a desperate search for similarity with one another, since physical/epistemological boundary breaks can be extrapolated to political boundary crossings. In fact Ebert (probably unwittingly) echoes Haraway's call to shifting and indeterminate boundaries when she notes, "Not only can one and should one speak for the other and with the other, but the other is not other."

Feminist_Politics@Second_Millennium: Carpe Cyborg?Why should feminists be concerned with Haraway's vision of the cyborg? There are two reasons: first, more literally, that the cyborg represents the world of technoscience which feminists must fearlessly enter and engage with; secondly, more metaphorically, that the cyborg represents a paradigm for collective political action. Haraway's (and my) concern is that some feminists are too quick engage in "anti-science metaphysics [and] demonology of technology" and so miss visionary as well as concrete possibilities. And truly, most scientific developments in the cyborg age do not spring innocently from the mind of a devoted and loving mad scientist who cares only for her art as she labours in obscurity; they are controlled and manipulated according to a global military-capitalist agenda of profit and knowledge control. Haraway is clear that she is aware of the problems of technoscience, and coins the term "New World Order, Inc." to describe the worldwide technoscience industry. She notes: "?I think the conclusion that the technoscientific agenda for everybody is set by the economically dominant powers, especially the United States, is inescapable." She lists the concerns of those who oppose such practices as the creation of transgenic organisms: The objections include increasing capital concentration and the monopolization of the means of life, reproduction, and labour; appropriation of the commons of biological inheritance as the private preserve of corporations; the global deepening of inequality by region, nation, race, gender, and class; erosion of indigenous peoples? self-determination and sovereignty in regions designated as biodiverse while indigenous lands and bodies become the object of intense gene prospecting and proprietary development; inadequately assessed and potentially dire environmental and health consequences; misplaced priorities for technoscientific investment funds; propagation of distorted and simplistic scientific explanations, such as genetic determinism; intensified cruelty to and domination over animals; depletion of biodiversity; and the undermining of established practices of human and non-human life, culture and production without engaging those most affected in democratic decision-making. Aware as Haraway is of objections, she nevertheless cautions that "[e]ffects and practices are context-specific, and it is too easy for all parties to fall into dogma where fundamental cultural and material values are both not shared and at stake." All parties taking part in the technoscience debate must not forget that "power, profit and bodily rearrangements are at the heart of biotechnology as a global practice." In other words, activists should not mount a defense against technoscience which relies upon "a problematic argument resting on unconvincing biology? [wherein] a kind of timeless stasis in nature is piously narrated", but aim instead at the economic systems of technoscience while increasing collective scientific expertise. While Haraway is speaking here specifically of debates around biotechnology, the objections raised can be extrapolated to larger technoscientific fields. But one should not throw the baby out with the bathwater, since tangled in the mess of corporate profit, patenting, and power is some kind of actual scientific practice which may, however painfully, be extricated and used by "us" instead of/as well as "them". Though a scientific development such as the Internet sprung from Cold War military machinations, it has escaped, mutated, and spawned itself so that now feminists may use it to their advantage. The former war toy is now a useful feminist tool. Granted, it is a tool available to precious few, but once its possibilities were realized, feminists began campaigning for the presence of free public computers in accessible locations such as universities and community libraries. Despite many well-founded concerns, Haraway believes in the transformative potential of technoscientific practice for feminists. After all, "[d]azzling promise has always been the underside of the deceptively sober pose of scientific rationality and modern progress within the culture of no culture." Visionary potential aside, it is clear that feminists must engage with technoscience or risk being omitted from the discourse and practice; if we choose deliberate ignorance the gap between "us" and "them" (propagators and proponents of New World Order, Inc.) will only further widen and leave us incapable of mounting an intervention, defense, or transformation. Haraway points out: We [feminists] unmasked the doctrines of objectivity because they threatened our budding sense of collective historical subjectivity and agency and "embodied" accounts of the truth and we ended up with one more excuse for not learning any post-Newtonian physics and one more reason to drop the old feminist self-help practices of repairing our own cars. They?re just texts anyway, so let the boys have them back. Besides, these textualized modern worlds are scary? Haraway is critical of feminist avoidance of technoscience, particularly since she feels the meeting is inevitable: "Like it or not, I was born kin to 239Pu* and to transgenic, transspecific, and transported creatures of all kinds? It will not help---emotionally, intellectually, morally, or politically, to appeal to the natural and the pure." Thus Haraway and I believe that we as feminists must explore and adopt scientific expertise not only to intercept its destructive branches but to create new avenues of inquiry. What would a feminist scientific practice look like, or more correctly, a socialist feminist practice, since that is the project which Haraway adheres to? Ebert here might make the critique that a feminist scientific intervention must necessarily be restricted to the activities of a small group of bourgeois women with the education and the means to play in the lab. I think this vision of the feminist role is too narrow. A socialist feminist scientific practice would not restrict its activities to nunnish cloistered research, but would engage in a critical discourse around scientific practices and processes worldwide, from the electronics sweatshops in Singapore to the hiring practices of science faculties in Western universities. Feminists have stakes in a successor science project that offers a more adequate, richer, better account of a world, in order to live in it well and in critical, reflexive relation to our own as well as others? practices of domination and the unequal parts of privilege and oppression that make up all positions? So I think my problem and "our" problem is how to have simultaneously an account of radical historical contingency for all knowledge claims and knowing subjects, a critical practice for recognizing our own "semiotic technologies" for making meanings, and a no-nonsense commitment to faithful accounts of a "real" world, one that can be partially shared and friendly to earth-wide projects of finite freedom, adequate material abundance, modest meaning in suffering, and limited happiness? Feminists don't need a doctrine of objectivity that promises transcendence, a story that loses track of its mediations just where someone might be held responsible for something, and unlimited instrumental power? we do need an earth-wide network of connections, including the ability to translate knowledges among very different?and power-differentiated?communities. If, as Haraway asserts, "science is cultural practice and practical culture", then it can be changed, shaped, modified, interrupted and redirected. It is up to a socialist-feminist technoscience to lay bare the global-military-corporate agenda, work to subvert it, and seek new avenues of inquiry. This brings us to the second aspect of Haraway's cyborg vision: its use as a metaphoric paradigm for political action. Haraway writes: "[M]y cyborg myth is about transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities which progressive people might explore as one part of needed political work." The physical reality of the liminal cyborg self translates into a framework for action which also encompasses partiality, boundary transgressions, contradiction, and fracture. There is no pretense to unity or singularity; in fact such aspirations are not focused but myopic, as well as dangerous: "Single vision produces worse illusions that double vision or many-headed monsters." The lesson that many feminists have learned is that feminist systems based on a monolithically guiding concept are not only exceedingly limited in scope and application, but also that diversity and difference are punished. "Taxonomies of feminism produce epistemologies to police deviation from official women's experience." As a result, theories and systems lose their utility for collective political action. This is not to endorse the cyborg heartily as a utopic vision. Haraway is very clear that we must enter the cyborg politic with eyes wide open, and be aware of its agenda: From one perspective, a cyborg world is about the final imposition of a grid of control on the planet, about the final abstraction embodied in a Star Wars apocalypse waged in the name of defense, about the final appropriation of women's bodies in a masculinist orgy of war. Yet the cyborg can represent other, more positive things (the advantage, of course, of having multiple selves). Haraway hopes to use the cyborg to represent "lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints." The solution for her is to see with plural vision; to be aware and critical of both birth-and-death aspects of the cyborg in the development of political struggle. What are the effects of advocating a cyborg politics upon feminist identities? Many battles have been fought in the feminist community over problems of identity?from what standpoint should one speak, if at all? The problem, of course, is that "[i]t has become difficult to name one's feminism by a single adjective?Consciousness of exclusion through naming is acute. Identities seem contradictory, partial and strategic." The question becomes: who do I ally myself with?who becomes the us and them of my politics? And then: what do I do when this tenuous collectivity based on an imagined self becomes fragmentary, or when I realize that I have defined "us" as "not-them" and the "them" has shifted so that my negation is meaningless? Finally, most shameful: what do I do when a part of the "us" happens, secretly or otherwise, to be aligned with "them"? I could make an attempt to devise some kind of naturalized self, as if through reaching back into my imagined ontology it would become clear in which camp I should be pitching my tent. This desire for ontology is not to be entirely derided, for it often serves as a necessary component in a political consciousness, process and development. After all, for the search for a rock foundation is much more comfortable than acknowledging that all around me is nothing but shifting sand. But once I realize that I can find no such rock of identity, I am forced to acknowledge the "limits of identification" in political consciousness and begin to explore my own contradictory consciousness as I ask: "What kind of politics could embrace partial, contradictory, permanently unclosed constructions of personal and collective selves and still be faithful, effective?and ironically, socialist-feminist?" Thus the old static categories which were useful determinants in the past of "us" and "them" are "all in question ideologically. The actual situation of women is their integration/exploitation into a world system of production/reproduction and communication called the informatics of domination." Identity politics?or rather, monolithic identity politics which do not account for shifts and partialities?are no longer effective when identities are constantly being reworked. Haraway suggests instead a politics of affinity and "kinship"?not kinship in the most literal sense, but in the manner of recognizing that our travels across this political plane can make for strange bedfellows. In the same way that we must invite drunken Uncle Louie or mad Aunt Tillie to our wedding because they are related to us, we must invite OncoMousetm and 239Pu to our politics because they are our weird extended family of the cyborg age.

Marxism in the machineTeresa Ebert, in her chapter "Cyborgs, Lust and Labour", provides a Marxist-based critique of Donna Haraway's cyborg. To begin with, she does not believe Haraway's claim that this is a new age requiring new politics and paradigms. She states that "the argument for a postindustrial society is an argument for displacing the economic and suppressing Marx's theory of the mode of production and labour value." Ebert feels that Haraway's theories obscure the role of capitalism within the realm of technoscience, that her analysis "replaces advanced capitalism" with a diffuse sociocultural network of relations, and that she "substitutes de facto technological determinism for? a Marxist economic determinism, a technical matterism for a historical materialism." While it is true that Haraway does not focus as much as Ebert on economics, partially because her writing in the "Cyborg Manifesto" is intended to be visionary, it is too hasty to dismiss her writings as ignorant of lived economic relations. She does not, as Ebert alleges, "[erase] the very real material conditions of science and technology [and obscure] the fact that they are capitalist science and technology." In fact Haraway has been concerned extensively with the naturalization and self-erasure of a capitalist agenda which micro-inscribes itself into animal biology and macro-inscribes itself onto the labour relations of technoscience. In one of her earlier essays on animal biology, Haraway writes: Theories of animal and human society based on sex and reproduction have been powerful in legitimating beliefs in the natural necessity of aggression, competition, and hierarchy? It is not an accident of nature that our social and evolutionary knowledge of animals, hominids, and ourselves has been developed in functionalist and capitalist economic terms. And, in the essay titled "The Biological Enterprise: Sex, Mind, and Profit from Human Engineering to Sociobiology", Haraway is more explicit: Science is about knowledge and power? I would like to investigate how the field of modern biology constructs theories about the body and community as capitalist and patriarchal machine and market? I would like to explore biology as an aspect of the reproduction of capitalist social relations? [t]hat is, I want to show how sociobiology is the science of capitalist reproduction. And as if anticipating Ebert's criticisms, Haraway invokes Marx as applicable to technoscientific intervention: "As Marx showed for the science of wealth, our reappropriation of knowledge is a revolutionary reappropriation of a means by which we produce and reproduce our lives." In fact Marx appears often in Haraway's writing as a figure of ironic political myth himself: partially helpful, partially responsible for problematic adherence to a valid but reductionist ontology of domination. "Marxist starting points offered tools to get to our versions of standpoint theories, insistent embodiment, a rich tradition of critiques of hegemony without disempowering positivisms and relativisms, and nuanced theories of mediation." However, Haraway is critical of using Marxism to essentialize "the ontological structure of labour." Ebert takes issue with Haraway upon this point, arguing that "the extraction of surplus labour is an objective historical practice in class societies: it is historical, not ontological." But Haraway's main critique of Marxism's utility for collective social action is that "neither Marxist nor radical feminist points of view have tended to embrace the status of a partial explanation; both were regularly constituted as totalities." Perhaps the reason why Ebert finds Haraway so objectionable is that Ebert does not deal in partialities, but feels that "[s]urplus labour is the unsurpassable objective reality of class societies, and on this objective reality? depends the oppression of women? as well as the struggle for emancipation." This is clearly in opposition to Haraway's call for multiple identities, which might result in activists recognizing their place within the labour framework but also recognizing that they exist as more than the sum of their working parts. After all, where else but in Haraway's paradigm could one situate Ebert's example of professors who identify with the working class?a clear example of straddling "us" and "them" in contradictory consciousness? Additionally, Haraway is concerned with the use of "the vantage points of the subjugated" as the new form of feminist objectivity: [T]here is good reason to believe vision is better from below the brilliant space platforms of the powerful? But here lies a serious danger of romanticizing and/or appropriating the vision of the less powerful while claiming to see from their positions? The positionings of the subjugated are not exempt from critical re-examination, decoding, deconstruction, and interpretation; that is, from both semiological and hermeneutic modes of critical inquiry. The standpoints of the subjugated are not "innocent" positions. On the contrary, they are preferred because in principle they are least likely to allow denial of the critical and interpretive core of all knowledge. They are savvy to modes of denial through repression, forgetting and disappearing acts?ways of being nowhere while claiming to see comprehensively. Haraway, echoing her criticism of "single vision", further develops the metaphor of cyborg vision by noting: "The ?eyes? made available in modern technological sciences shatter any idea of passive vision?" In other words, to fetishize, as Ebert often does, the perspective of the subjugated as the new objectivity can be as problematic as assuming the objectivity of the scientific elite (the "modest witness" to the unfolding scientific process). "Only those occupying the positions of the dominators are self-identical, unmarked, disembodied ? it is unfortunately possible for the subjugated to lust for and even scramble into that subject position?and then disappear from view." Cyborg political vision must fold inward and outward upon itself multiply and self-reflexively, like the artist who must assume "aesthetic distance" from her work in order to properly critique it. "A commitment to mobile positioning and to passionate detachment is dependent on the impossibility of innocent ?identity?? ?Being? is? problematic and contingent." Here again the multiplicity of the cyborg is important for understanding and achieving partiality, critique, messiness, contradictions.

Problems of CodingEbert takes particular exception to Haraway's description of a problem of coding, suggesting that Haraway has "dematerializ[ed] technology as ?coding?, that is, discourse." While it is true that Haraway writes: "[C]ommunications sciences and modern biologies are constructed by a common move?the translation of the world into a problem of coding", to read her as advocating a discursive shift alone is simplistic and does not do justice to Haraway's complex vision. Moreover, Haraway points out in "Situated Knowledges" that "[t]he form in science is the artefactual-social rhetoric of crafting the world into effective objects." Haraway is clear that her myth has both physical and metaphysical implications, and that in many ways she is merely describing what is already in place. For example, in the field of medicine, particularly in genetic engineering, human beings (as well as plants and animals) can be translated into DNA protein codes which, if manipulated a certain way, will yield the desired result. So a concrete phenomenon such as aging is understood as a characteristic of the arrangement and flow of the DNA codes. The race is on among the baby boom generation to discover the perfect supplements or combination thereof which will help them live forever. Extropians, as many who seek extreme longevity call themselves, are busily munching down hundreds of products derived from bizarre and probably endangered sources in an effort to find the Rosetta Stone for their hieroglyphics of aging. In Modest_Witness, Haraway reproduces an advertisement for Operon DNA, which for a negligible $2.80 per sequence "makes anything possible", even the pictured "applorange" and "zucchana" which are pieced together presumably by some lip-smacking laboratory gourmand seeking the perfect stir-fry ingredients. It is merely a small leap of imagination to visualize the human Shakespeare plays emerging from the thousands of lab monkeys at their DNA typewriters. Tinker with the codes, re-direct their flow and energies, and one alters organisms on the basic physical level. On the macroscopic level, meteorologists and terrestrial scientists are busily labouring over the translation of Earth's climate and features into formulae to better predict the weather five days or five million years from today, while quantum physicists inscribe the anarchic processes of the universe into brief histories of time. There is no longer a sense among 20th century societies that we cannot know the workings of the divine; presently we regard the riddles of the inner and outer cosmos not as the obscure workings of an invisible deity's hand but as a cryptogram that merely requires the correct magic decoder ring. Haraway is, however, fully cognizant of the capitalist agenda of "coding" or systems theory and outlines the relationship in "Sex, Mind, and Profit". She explains how "[o]rganic form, with its hierarchical and psychological co-operation and competition based on ?natural? domination and division of labour, gave way to systems theory with its control schemes based on communications networks and a logical technology in which human beings become potentially outmoded symbol-using devices.? The problem which systems theory addressed was the maintenance and maximization of profit in crisis-ridden post-Second World War capitalism? it is a striking fact that the formal theory of nature embodied in sociobiology [and technoscience] is structurally like advanced capitalist theories of investment management, control systems for labour, and insurance practices based on population disciplines. From sociobiological systems theory developed the idea that the human body was just a walking container for the genes, which functioned in the manner of a capitalist military organization concerned only with efficiency and systems optimization. No longer was human (or animal) behaviour a function of their psyche, class position, breeding, or whatever the Victorian scientists had come up with; rather behaviour and form conformed to the genetic "capitalist dynamic of private appropriation of value and the consequent need for a precise teleology of domination?"

Thus the problem of coding which Haraway describes is not an endorsement but a recognition of capitalist systems theory which inscribes itself onto ideology and cultural practice/practical culture?technoscience. While this kind of discourse may not change actual social relations (which is arguable), it certainly changes the way we think about them and hence the way we experience them. Suggesting that breast cancer, criminal tendencies or mental illnesses have genetic components allows us to believe that people who are ill or criminal are merely improperly coded, and that if we just knew in advance of their faulty genetic Lego piece, then the code could be corrected and the problem would be solved. Feminists must be aware of this problem of coding, since according to Haraway, "[o]nly material struggle can end the logic of domination? in the form of? technologies of command-control systems fundamental to patriarchy. To the extent that these practices inform our theorizing of nature, we are still ignorant and must engage in the practice of science."

Whither Cyborg/Cyborg Dreams"Can cyborgs? or technological vision hint at ways that the things many feminists have feared most can and must be refigured and put back to work for life and not death?" The archetypal figure that Haraway has chosen to affiliate with the cyborg is the folk icon of the Trickster. The Trickster is a shape-shifter, jokester, idiot-savant, deviant oracle, perverse prophet. The Trickster embraces chaos and ambiguity and constantly reminds the Modest Witness that nothing is as it seems. Man [sic] was hardly imagined before he lost his place; nature was barely tamed before she took her revenge; the empire was barely consolidated before it struck back. The action in technoscience mixes up all the actors? [P]urity of all kinds, the great white hope of heliocentric enlightenment for a truly autochthonous Europe, the self-birthing dream of Man, the ultimate control of natural others for the good of the one?all dashed by a bastard mouse? Maybe in these warped conditions, a more culturally and historically alert, reliable, scientific knowledge can emerge. In other words, feminists, scientists, and feminist scientists need the "polymorphous perversity" of the cyborg trickster to avoid the capitalist autotelos and engage in both critical science and effective politics. "My modest witness?", writes Haraway, "is seeking to learn and practice the mixed literacies and differential consciousness that are more faithful to the way the world, including the world of technoscience, works."

BibliographyEbert, Teresa. Ludic Feminism and After: Postmodernism, Desire and Labor in Late Capitalism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press;1996. Haraway, Donna. Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleManc_Meets_OncoMousetm: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge; 1997. Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. New York: Routledge, 1991. Kunzru, Hari. "You Are Borg: For Donna Haraway, we are already assimilated", Wired 5.02 (Feb. 1997). Shlein, Bernard; Terpilak, Michael. The Health Physics and Radiological Health Handbook. Maryland: Nucleon Lectern Associates; 1984.

|

||||

|

|

|

||